René Descartes (1596-1650)

Widely regarded as a foundational figure in modern philosophy, Descartes profoundly shaped discussions

of the mind-body problem. Seeking certainty in an age of intellectual upheaval, he employed methodical

doubt, systematically questioning all beliefs derived from the senses or even mathematics.

His quest led him to one indubitable truth: his own existence as a thinking entity, famously

encapsulated in the dictum, "Cogito, ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am"). From this bedrock

of certainty, Descartes argued for substance dualism: a fundamental distinction between two kinds of

substance. The mind, or res cogitans (thinking substance), is characterized by thought and

lacks spatial extension. The body, or res extensa (extended substance), is characterized by

physical extension and lacks thought.

This sharp division immediately posed the interaction problem: if mind and body are fundamentally

different, how do they causally interact? How can non-physical thoughts lead to physical actions, or

physical sensations cause mental experiences? Descartes proposed the pineal gland in the brain as the

site of interaction, a specific physiological solution that is no longer accepted.

Despite criticisms of his specific interaction mechanism, Descartes' formulation of the mind-body

problem and his dualistic framework set the terms for philosophical debate for centuries. The intuitive

feeling that subjective experience has qualities irreducible to physical descriptions means dualistic

lines of thought continue to resonate, echoing the challenges inherent in bridging the Cartesian divide.

John Searle (1932-present)

An influential American philosopher, John Searle offers a distinct perspective within materialist

thought, known for his critique of computational theories of mind and his defense of "biological

naturalism." While accepting that mind is physical, he challenges views that reduce consciousness merely

to computation or function.

Searle famously targeted strong AI—the claim that running the right program is sufficient for genuine

understanding or consciousness—with his "Chinese Room" thought experiment. He imagined himself in a room

manipulating Chinese symbols according to formal rules (a program), producing syntactically correct

outputs without understanding the meaning (semantics) of the symbols. He argued this demonstrates that

symbol manipulation based on syntax alone does not guarantee understanding, undermining functionalist

and computational theories that equate mind with implementing the right program.

Instead of dualism or pure functionalism, Searle advocates "biological naturalism." This is the view

that consciousness is a real, irreducible, higher-level biological feature produced by the specific

causal powers of brain activity, much like liquidity is a feature of water molecules or digestion is a

feature of the stomach. Consciousness is entirely natural and biological, but cannot be reduced simply

to the physical components or their abstract functional organization.

Searle also emphasizes intentionality—the capacity of mental states to be *about* things in the world—as

a genuine biological capacity of the brain. By arguing that consciousness is real, irreducible, yet

entirely biological and dependent on specific brain properties, Searle carves out a unique position that

rejects both non-physical explanations and purely computational reductions of the mind.

Empiricist Approaches

Understanding the mind through experience and observation.

John Locke (1632-1704)

A pivotal figure in empiricism, John Locke profoundly influenced theories of knowledge, self, and

consciousness. He famously proposed that the mind at birth is a "tabula rasa" (blank slate),

rejecting the rationalist notion of innate ideas. Locke argued that all knowledge derives from

experience, obtained either through sensation (external perception) or reflection (internal awareness of

the mind's operations).

In his seminal work "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding," Locke distinguished between simple ideas,

received directly from experience, and complex ideas, formed by the mind through combining, comparing,

and abstracting from simple ones. He also differentiated primary qualities (like size, shape, motion),

believed to exist objectively in objects, from secondary qualities (like color, taste, sound), which

depend on the perceiver's mind.

Crucially, Locke grounded personal identity not in the persistence of a physical or mental substance,

but in the continuity of consciousness, specifically through memory. For Locke, what makes an individual

the same person over time is the ability of their present consciousness to extend back and connect with

past thoughts and actions via memory. "As far as this consciousness can be extended backwards... so far

reaches the identity of that person." This emphasis on psychological continuity remains highly

influential in contemporary discussions of personal identity, linking the self inextricably to memory

and awareness.

David Hume (1711-1776)

The Scottish philosopher David Hume pushed empiricism to its logical, and arguably radical, conclusions,

leading to profound skepticism about the self, causation, and inductive reasoning. He maintained that

all mental contents are either vivid impressions (sensations, passions, emotions) or fainter ideas

(copies of impressions used in thinking). Every simple idea, he insisted, must derive from a

corresponding simple impression.

Applying this principle rigorously through introspection, Hume famously reported finding no impression

of a persistent, unified self. Instead, he observed only a constant flux of particular perceptions—heat

or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. "When I enter most intimately into what I

call myself," he wrote, "I always stumble on some particular perception... I never can catch

myself at any time without a perception..." This led to his influential "bundle theory": the

"self" or "mind" is not a distinct substance but merely "a bundle or collection of different

perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and

movement."

Hume extended his skeptical analysis to causation, arguing that we never perceive a necessary connection

between events, only their constant conjunction (one event regularly following another). Our belief in

cause-and-effect arises from habit or custom, not rational insight. Similarly, he argued that our belief

in personal identity over time is not based on perceiving an unchanging self but is a product of the

imagination, facilitated by memory, linking the succession of perceptions together. Hume's focus on

experience paved the way for later scientific psychology, while his skepticism continues to challenge

philosophical assumptions about the foundations of knowledge and the nature of the self.

William James (1842-1910)

A pioneering American figure in both psychology and philosophy, William James offered a highly

influential description of conscious experience that moved away from static, atomistic analyses. He

criticized approaches that tried to break consciousness into discrete elements, arguing this distorted

the fluid nature of lived experience.

In his major work "The Principles of Psychology," James famously described consciousness as a "stream."

This metaphor captured key characteristics observed through introspection: consciousness is personal

(always belonging to someone), constantly changing (never the exact same state twice), continuous

(feeling like it flows despite gaps like sleep), and selective (attending to some objects while ignoring

others). "Consciousness... does not appear to itself chopped up in bits... it flows." This dynamic

characterization provided a richer, more phenomenologically accurate picture of subjective life.

James also made important contributions to the study of memory, distinguishing between primary memory

(immediate awareness, akin to modern working memory) and secondary memory (the larger store of past

knowledge recallable into consciousness). His distinction highlighted memory's role in both constituting

the present moment and connecting it to the past.

Consistent with his pragmatist philosophy, James viewed consciousness functionally. He believed it

evolved because it serves adaptive purposes, helping organisms navigate their environment, make choices,

and respond flexibly. This focus on what consciousness *does* represented an early form of functionalist

thinking, bridging purely mental accounts with biological and evolutionary considerations.

Transcendental Idealism

How the Mind Structures Experience

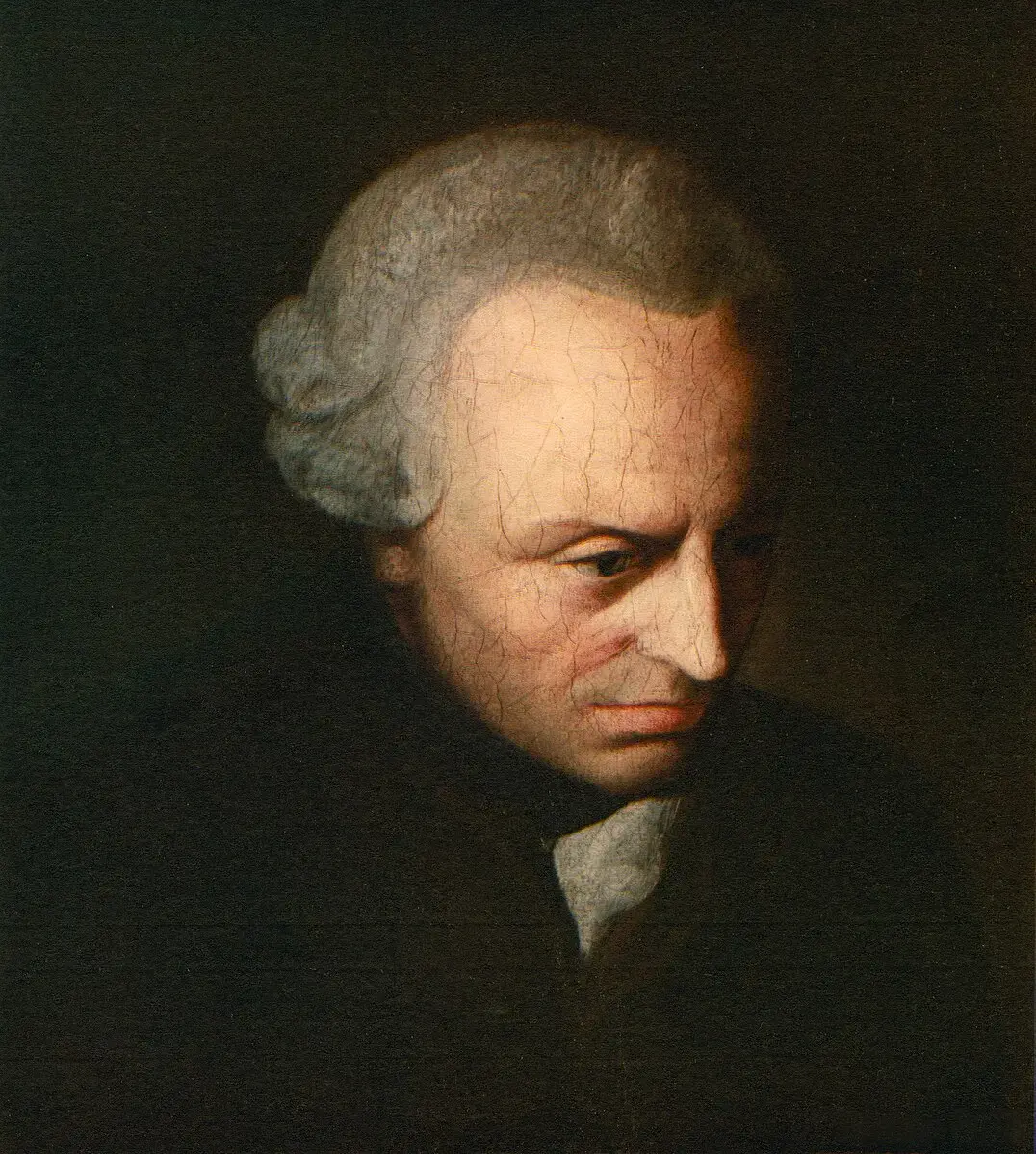

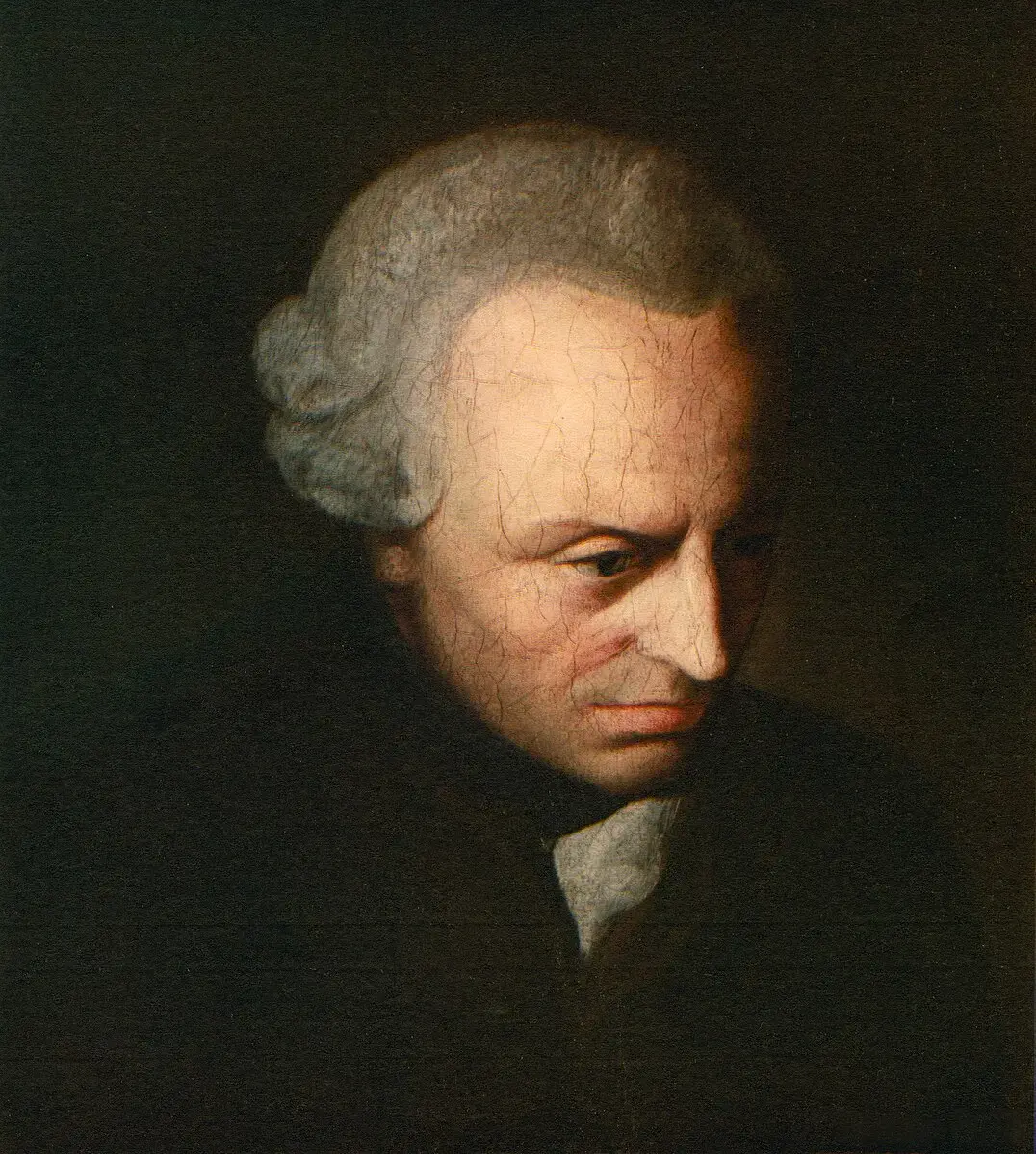

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant undertook a monumental project to resolve the impasse between

rationalism and empiricism, introducing a "Copernican Revolution" in philosophy. He acknowledged the

empiricist claim that all knowledge begins with experience but rejected the idea that the mind is merely

a passive recipient. Instead, he argued that the mind actively contributes necessary structures that

make objective experience possible.

In his "Critique of Pure Reason," Kant presented transcendental idealism. He argued that fundamental

features of our experience, such as space and time, are not properties of things-in-themselves (the

*noumenal* world) but are necessary forms of our sensibility—innate ways our mind structures sensory

input. Similarly, concepts like causality, substance, and unity are not derived from experience (as Hume

argued) but are innate categories of the understanding—rules the mind imposes to organize sensations

into a coherent, objective *phenomenal* world. Thus, the mind actively shapes the reality we experience.

Central to Kant's account is the "transcendental unity of apperception." This is the requirement that

all of my experiences must be capable of being accompanied by the "I think." For an experience to be

*mine*, it must be possible for me to recognize it as such. This unity is not an empirical finding but a

necessary precondition for any coherent experience. This "I think" is not a substantial soul (Descartes)

nor a mere bundle of perceptions (Hume), but represents the underlying unity of self-consciousness that

makes experience possible—the logical subject or viewpoint from which experience is organized.

Kant's ideas profoundly influenced subsequent philosophy. His emphasis on the mind's active role in

structuring experience anticipates modern cognitive science's view of perception as a constructive

process. Furthermore, his focus on the necessary unity of consciousness identifies a key feature that

contemporary scientific theories (like Integrated Information Theory and Global Workspace Theory)

attempt to explain mechanistically. Kant provided a framework highlighting structural requirements for

conscious experience.

Materialist Views

Explaining consciousness as a physical phenomenon.

Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709-1751)

A French physician and philosopher, La Mettrie presented one of the earliest and most uncompromising

materialist accounts of the mind during the Enlightenment. Drawing on medical observations, he radically

challenged prevailing views, particularly Cartesian dualism.

In his provocative work L'Homme Machine ("Man a Machine"), La Mettrie argued forcefully that

humans, including their mental faculties, are nothing more than complex physical mechanisms. He

contended that phenomena like consciousness, memory, and thought could be explained solely by the

physical workings of the body, particularly the brain. Observing how illness and substances affected

thought and emotion, he concluded that the "soul" was merely a term for the thinking aspect of our

physical organism.

La Mettrie's thoroughgoing materialism and hedonistic ethics were highly controversial in his time,

forcing him into exile. Though often dismissed then, his insistence on explaining the mind through

physical processes directly anticipated the central focus of modern neuroscience and cognitive science.

While his specific mechanistic explanations were rudimentary, La Mettrie's work represents a clear early

articulation of the materialist project. It also implicitly raises the persistent challenge that

materialism still faces: how exactly do purely physical processes generate subjective experience?

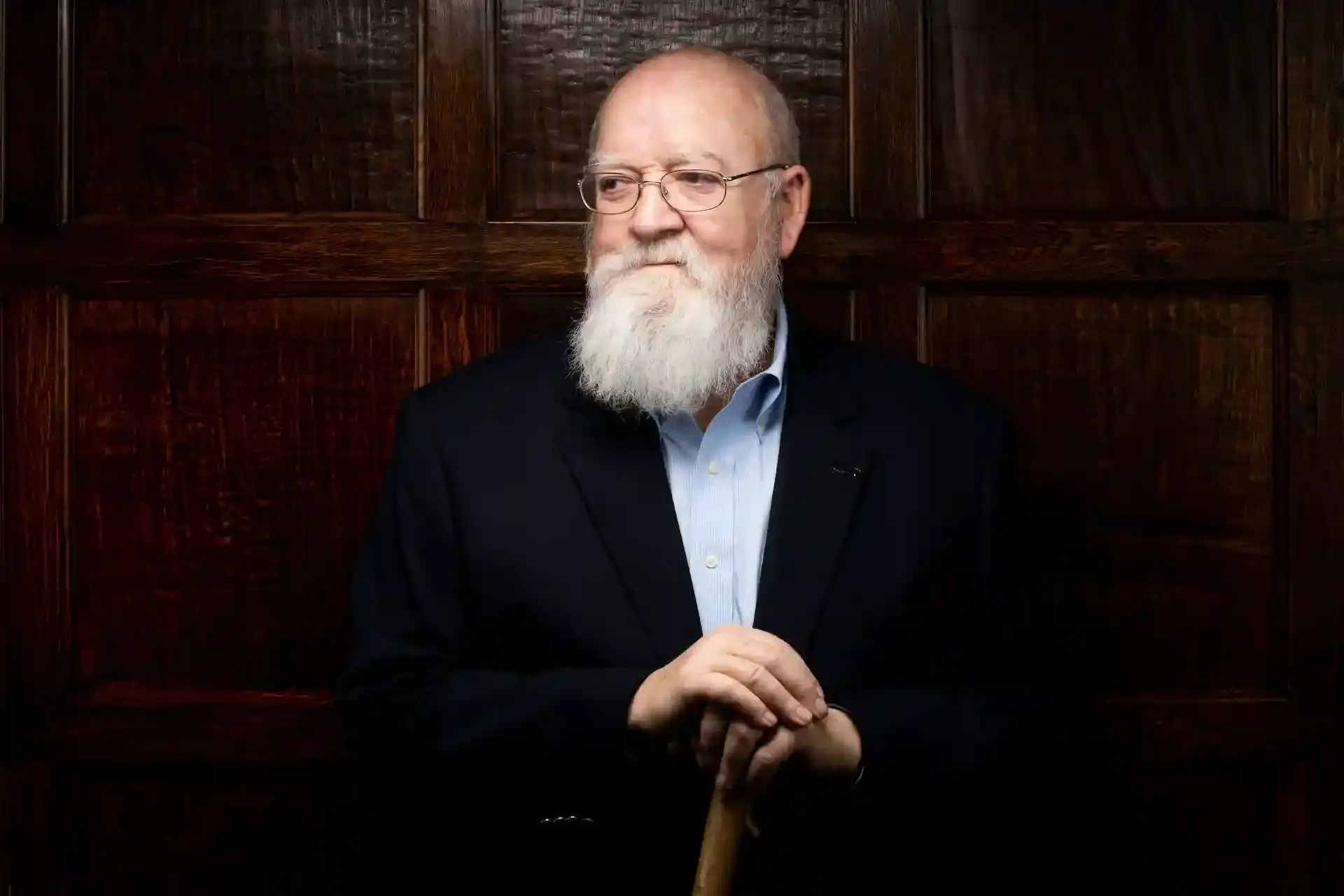

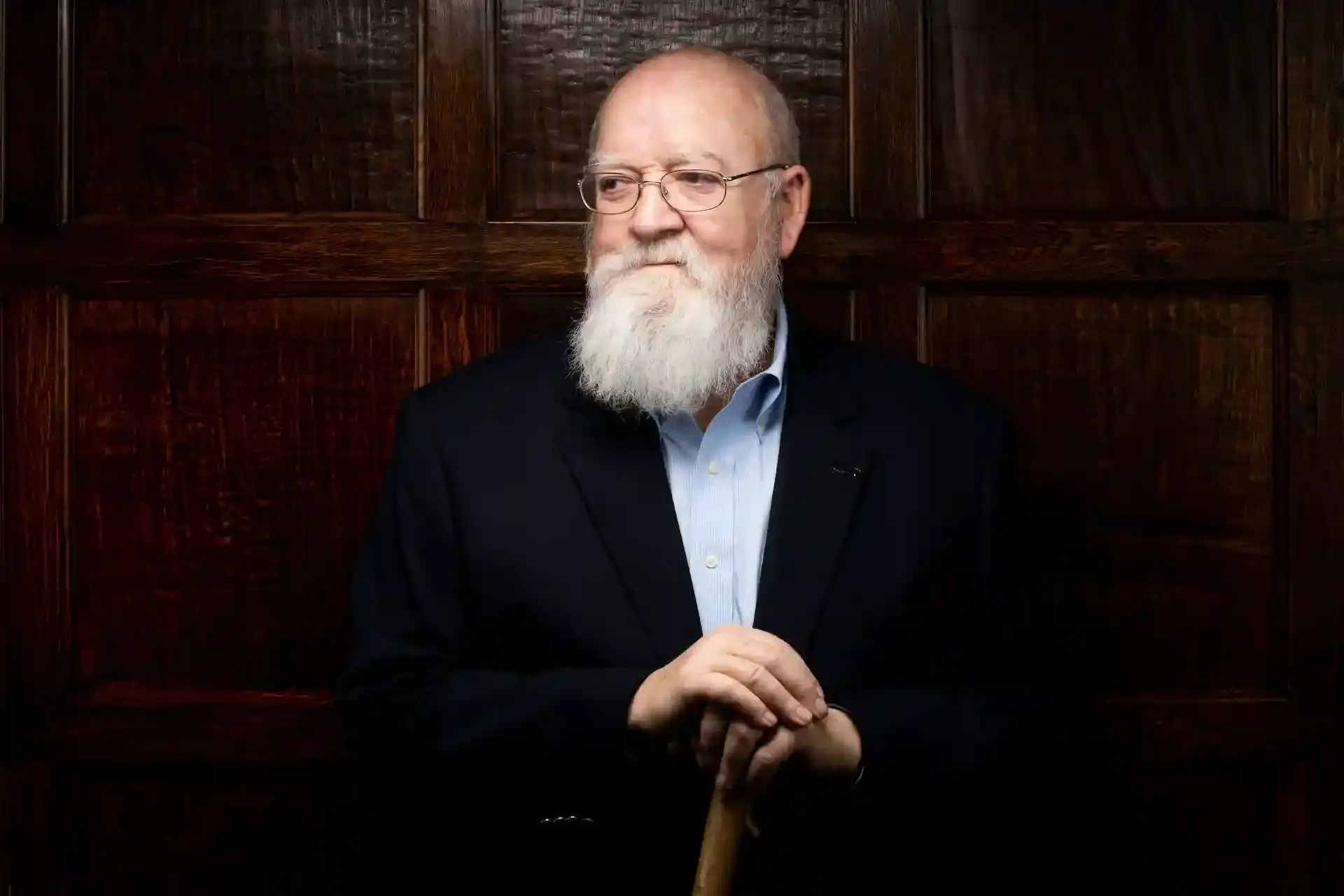

Daniel Dennett (1942-2024)

A prominent contemporary philosopher and cognitive scientist, Daniel Dennett was a leading advocate for

a functionalist and materialist understanding of the mind, strongly influenced by evolutionary biology

and computer science. He famously challenged intuitive notions about consciousness, arguing that many

perceived mysteries might dissolve under careful scientific scrutiny.

In works like "Consciousness Explained," Dennett proposed the "multiple drafts" model. He rejected the

idea of a single, unified center or "Cartesian Theater" in the brain where consciousness occurs.

Instead, he argued that consciousness emerges from numerous parallel, distributed information-processing

streams ("drafts") in the brain, constantly competing and being revised, with no definitive moment at

which a draft becomes "conscious." He suggested our sense of a rich, unified stream of consciousness

might be a kind of benign "user illusion" generated by these underlying processes.

Dennett viewed memory not as a faithful recording but as a fundamentally reconstructive process, prone

to error and revision. He also introduced the useful concept of the "intentional stance": we can

effectively predict and explain the behavior of complex systems (like humans, animals, or chess

computers) by attributing beliefs, desires, and intentions to them (treating them *as if* they are

rational agents), regardless of the underlying physical mechanisms or the ultimate metaphysical status

of these attributed states.

Dennett consistently argued against the idea of irreducible qualia or a "hard problem" of consciousness

that is fundamentally resistant to scientific explanation. While sometimes accused of "explaining away"

consciousness, his work provided a sophisticated defense of naturalism, aiming to integrate the mind

fully within a scientific worldview derived from thinkers like La Mettrie, but updated with insights

from modern science.

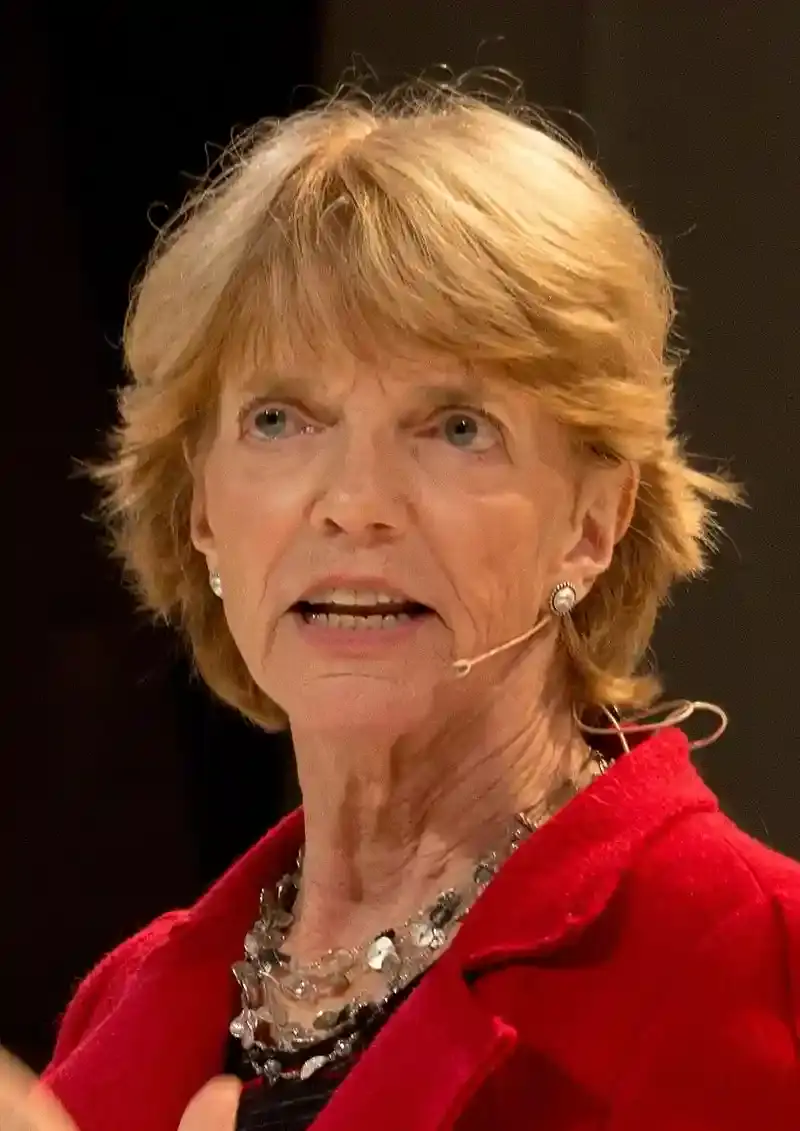

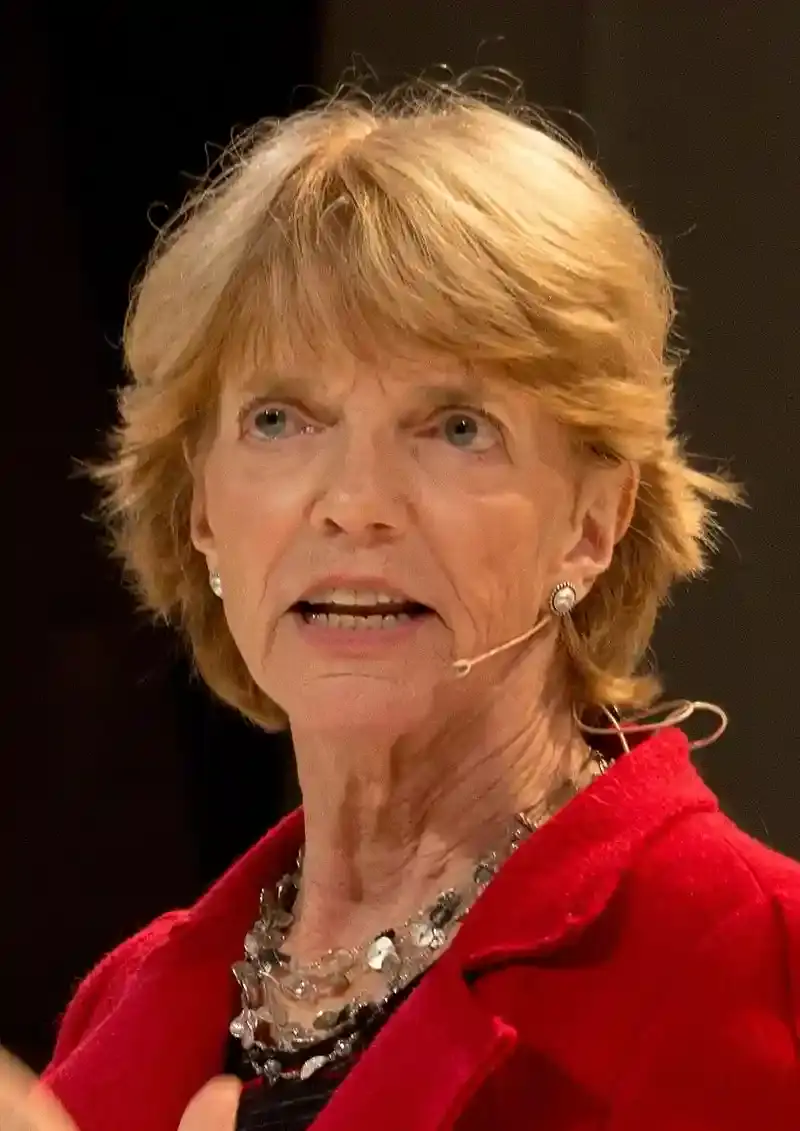

Patricia Churchland (1943-present)

A leading proponent of "neurophilosophy," Patricia Churchland advocates for a tight integration between

philosophy of mind and neuroscience. She argues forcefully that traditional philosophical methods

relying solely on introspection or conceptual analysis are insufficient, and that philosophical theories

about the mind must be informed by, constrained by, and potentially revised in light of empirical

findings about the brain.

Along with Paul Churchland, she defends eliminative materialism. This radical view proposes that our

common-sense psychological framework, termed "folk psychology"—which explains behavior using concepts

like beliefs, desires, intentions, fears, etc.—is not just incomplete but is actually a deeply flawed

empirical theory. Eliminativists argue that folk psychology fails to explain many mental phenomena (like

mental illness, sleep, learning, creativity), has stagnated scientifically, and is unlikely to map

neatly onto the actual neural processes discovered by neuroscience.

They predict that, much like outdated scientific concepts such as phlogiston or caloric fluid were

eliminated and replaced by better theories, the concepts of folk psychology will eventually be discarded

and replaced by a more accurate vocabulary derived directly from neuroscience. This contrasts with

reductionist materialism, which aims to *reduce* folk psychological states to brain states;

eliminativism seeks to *eliminate* them altogether as referring to anything real.

Regarding memory, Churchland emphasizes its biological basis, stressing that it comprises multiple,

distinct systems supported by different brain structures (e.g., memory for skills vs. facts vs. events).

These systems are seen as constructive, fallible, and operating according to neurobiological principles,

challenging simpler philosophical models of memory as passive storage. Churchland's approach represents

a strongly naturalistic and materialist perspective, viewing the mind as fundamentally what the brain

does, best understood through empirical investigation.

Contemporary Issues

Modern approaches to the challenges of explaining consciousness.

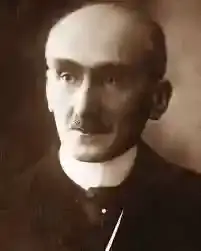

Henri Bergson (1859-1941)

The French philosopher Henri Bergson offered a unique perspective on consciousness and time, challenging

the dominant mechanistic and purely intellectual approaches of his era. Awarded the Nobel Prize in

Literature, Bergson emphasized the importance of intuition and the qualitative flow of inner experience.

In works like "Time and Free Will," Bergson famously contrasted objective, measurable clock time with

durée (duration)—the continuous, qualitative, heterogeneous flow of subjective experience. He

argued that the analytical intellect, which breaks things down into static, spatialized units,

inevitably distorts the indivisible mobility of real duration. This process creates a "cinematographic

illusion," mistaking a series of static snapshots for true, fluid becoming. True durée, he

believed, could only be grasped through intuition.

His theory of memory, presented in "Matter and Memory," was similarly distinctive. He distinguished

sharply between habit memory (learned bodily skills enacted automatically) and pure memory (souvenir

pur), which he conceived as the virtual totality of one's past experiences, preserved in their

unique temporal character. Bergson controversially suggested that pure memory might exist independently

of the brain, with the brain acting primarily as a filter or selection mechanism. Its role is not merely

storage, but to inhibit irrelevant memories and bring pertinent past experiences into contact with

present perception to guide action effectively.

Although his influence waned during periods dominated by analytic philosophy, Bergson's focus on the

qualitative, temporal richness of consciousness and his critique of purely analytical methods have seen

renewed interest. He offers a perspective that resists reducing the mind entirely to physical mechanisms

or static concepts, emphasizing the unique character of subjective, lived time.

Thomas Nagel (1937-present)

Thomas Nagel is a highly influential contemporary philosopher renowned for crystallizing the problem of

subjective experience in his seminal 1974 paper, "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?". He consistently

challenges physicalist reductionism, arguing that purely objective, third-person scientific accounts

inherently fail to capture the subjective, first-person perspective of conscious experience.

In the "Bat" paper, Nagel argued that even if we possessed complete physical knowledge about a bat's

neurophysiology and sonar system, we still wouldn't know *what it is like* to be that bat—to experience

the world through echolocation *from the bat's point of view*. This subjective character of experience,

the "what-it's-like-ness" often referred to as qualia, seems inherently tied to a specific perspective

and resistant to objective description. Nagel contends that physicalism, aiming for a purely objective

account, necessarily leaves out this essential dimension, creating an explanatory gap.

Nagel explores this tension between subjective and objective viewpoints across various philosophical

domains, including ethics and personal identity, notably in his book "The View From Nowhere." More

recently, in "Mind and Cosmos," he controversially questioned the adequacy of current neo-Darwinian

evolutionary theory and physical science to fully explain the emergence of consciousness, cognition, and

value in the universe, suggesting that the universe might possess inherent teleological principles.

While not advocating for traditional substance dualism, Nagel strongly argues that consciousness is a

real, fundamental phenomenon that current materialist science struggles to incorporate. His persistent

focus on the apparent irreducibility of the subjective perspective continues to fuel debates about the

mind-body problem, the nature of reality, and the ultimate limits of scientific explanation.

David Chalmers (1966-present)

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers is renowned for sharply formulating the distinction between

the "easy problems" and the "hard problem" of consciousness, significantly shaping contemporary

discussions in philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

Chalmers defined the "easy problems" as those concerning the explanation of cognitive functions

associated with consciousness: how the brain integrates information, focuses attention, controls

behavior, reports mental states, implements memory, etc. While complex, he argues these problems are

amenable, in principle, to standard methods of cognitive science and neuroscience—they concern

explaining functional abilities and mechanisms.

The "hard problem," in contrast, is the question of *why* and *how* any of this physical processing

should be accompanied by *subjective experience* or qualia. Why does information processing *feel like*

anything from the inside? Chalmers argues that this problem resists conventional reductive explanation

within a purely physicalist framework. Standard explanations might account for structure and function,

but not for the intrinsic experiential quality itself.

To bolster his case, Chalmers uses thought experiments like philosophical zombies—hypothetical beings

physically identical to humans but lacking any subjective experience—to argue that consciousness is not

logically entailed by physical or functional properties alone. This suggests that consciousness might be

a further, perhaps fundamental, feature of the world. While not a traditional substance dualist,

Chalmers has explored alternatives like property dualism (where consciousness is a fundamental,

non-physical property of certain complex physical systems) or even forms of panpsychism (where

consciousness, or proto-consciousness, is a fundamental property of matter itself). His work ensures the

"hard problem" remains a central focus of inquiry into the nature of mind and reality.